Gray skies bled into gray water as I snaked down the eastern shore of Lake Namakagon on County Highway D. After a hike with a friend, I’d decided to take the long way home. My dad used to tell us that drives like this were “shortcuts” although what he really meant is that they were the scenic route. He was usually looking for hawks on fence posts in the fields of Iowa. I spotted something quite different.

Out in the middle of Sugar Bay, a small shape interrupted the glimmering ripples. Even in the poor light at a fair distance from a moving car, I could tell that this was a loon by their distinctive silhouette. After a few seconds of indecision I swung into a gravel road and “flipped a Louie” which is what my family calls Uies or U-turns. Pulling safely off the road, I dug my new Natural Connections camera (thank you donors!) out of my backpack and zoomed in.

The loon’s gray-brown back, full white throat, and pale cheeks confirmed them as a juvenile, a young of this year. While this loon is on the late end of migration, I wasn’t worried for their safety. Juvenile loons have been navigating their fall migrations alone for millennia. The general schedule I’ve been told is that bachelor loons (without chicks for whatever reason) migrate in August, mother loons head out in September, the dad’s leave in October, and the juveniles fly south in November.

|

| Here's a clearer image of a juvenile loon on a sunny day in a previous late October. Photo by Emily Stone. |

That’s just a general schedule, though, and individual loons are likely all over the calendar, as well as the map. That also doesn’t account for loons from Canada making pit stops here along their way. Early ice formation will shoo them south faster, and warm autumns like this one don’t give them any reason to hurry.

The ultimate destination for loons is saltwater that doesn’t freeze. Their main habitat requirements are plenty of fish to eat and clear water to hunt in. Southern inland lakes tend to have warm, shallow, murky water, and alligators (!), so the ocean provides a better option. There, loons face the challenge of transitioning from freshwater to saltwater. They’ve adapted by excreting salt out of glands in their skull between their eyes. The glands drip almost constantly during the winter…sort of like how my nose adapts to winter, too…

After making the big journey and coping with salt, loons gain access to a seafood feast. Wintering loons eat flounder, crabs, lobster, shrimp, gulf menhaden, bay anchovies, silversides, and more. The ocean bounty gives loons enough energy to molt and regrow all of their feathers, which carry them back north in the spring.

Those feathers carry important information, too. As loon researcher Walter Piper recently wrote on his Loon Project blog, once feathers are grown, they don’t continue to be living tissue. Just like our fingernails, they stop receiving a blood supply and become a time capsule. Inside the feathers are stable isotopes, or as Piper explained, “different versions of a chemical element with different masses.” By studying the stable isotopes of the feathers and matching them to the stable isotopes of various loon wintering locations, we can identify the place where the feather was grown. When scientists capture a loon in Wisconsin in July, studying a tiny clip of a feather can reveal where that loon spent their winter.

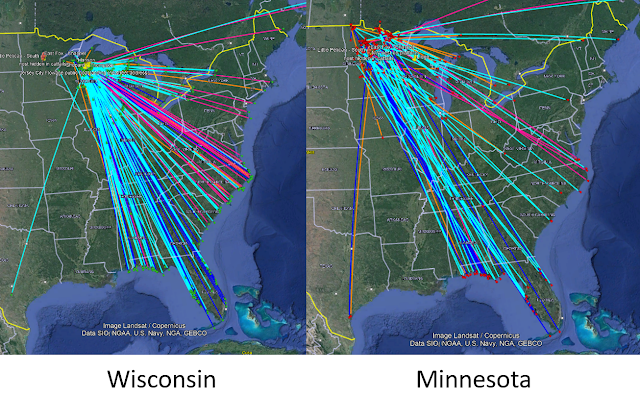

Early studies of loon migration using satellite transmitters suggested that many of our loons head to the west coast of Florida. Further information provided by recoveries and sightings of banded loons expanded that map quite a bit. We now have records of banded loons from Wisconsin and Minnesota wintering all along the west and east coasts of Florida, up through Georgia and the Carolinas, and even up into the Northeast, but that data is mostly based on luck.

|

| Loon migration patterns from the Loon Project blog. |

This new avenue of stable isotope analysis opens up a way for scientists to capture a loon on their breeding territory up here and figure out where they spent last winter without having to track them on migration. Why does that matter? Well, I for one, love talking to snowbirds about their winter adventures in warm places. But more importantly, this information may help scientists understand how challenges loons face over the winter may be impacting their ability to return north, or their breeding success once they get here.

Out on Sugar Bay, the feathers of that juvenile loon contain information from here, or maybe from Canada, wherever the kid molted out of their baby fuzz and into their first round of sleek feathers. After three or four years gaining strength and maturity on the ocean, this loon will molt into their striking black-and-white breeding plumage for the first time—feathers filled with the signature of saltwater—and fly home.

I wonder if they’ll take a “shortcut” or flip any Louies along the way!

Emily’s award-winning second book, Natural Connections: Dreaming of an Elfin Skimmer, is available to purchase at www.cablemuseum.org/books and at your local independent bookstore, too.

For more than 50 years, the Cable Natural History Museum has served to connect you to the Northwoods. Our exhibit: “The Northwoods ROCKS!” is open through mid-March. Our Fall Calendar of Events is ready for registration! Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and cablemuseum.org to see what we are up to.

No comments:

Post a Comment