“Every year we have been witness to it: how the world descends into a rich mash, in order that it may resume.”

By Mary Oliver, from “Lines Written in the Days of Growing Darkness”

Our glorious fall colors are drifting to the ground, lying thick in the woods and the edges of our yards that we’ve set aside for wild things. Their thin bodies will protect queen bees, wood frogs, and firefly larvae, and become a rich mash that feeds new growth in the spring.

|

| These frosty leaves may be dead, but they are both food and protection for many still-living things in the ecosystem. Photo by Emily Stone. |

For now, the year is transitioning toward dark days and gray thoughts. We are at the half-way point between the Autumn Equinox and Winter Solstice. Also known as a “cross-quarter day,” many cultures believe that October 31 and November 1 are days when the boundary between this world and the next is more easily crossed. As plants senesce, insects freeze, and hunting seasons begin, death surrounds us.

My identity as a naturalist informs the way I think about the world more than any other influence. Naturalists seek to observe the interconnected relationships between living and non-living beings so we can understand the past, present, and future of our local and cosmological environments. It is within this framework that I think about death, reincarnation, and everlasting life.

When my dear Aunt Nan died, a poem called “Wings” by Mary Oliver became a comfort to me. It is about a great blue heron. The last lines are: “my bones knew something wonderful about the darkness--and they thrashed in their cords, they fought, they wanted to lie down in that silky mash of the swamp, the sooner to fly.”

Poems are often metaphors, filled with symbolism, but as a naturalist I recognize the truth in these words. Swamps are cradles of both decomposition and of new life. If Nan, I, or anyone were to lie down in “that silky mash of the swamp,” efficient teams of bacteria would dismantle our bodies bit by bit back into their component parts, and they would get passed, bit by bit, up the food chain. Soon, they might become part of a heron. And when those powerful wings rise into the sky, atoms who were once part of our bodies rise, too.

Of course, if you ask Nan, the wings that carry her skyward belong to a dragonfly. Nan told us that she would come back as a dragonfly, or rather, as ALL dragonflies. By giving us this touchstone, Nan ensured that she’d continue to be present in our hearts and minds.

This concept is well stated by the Greek philosopher Pericles, whose quote is in the sympathy cards I always keep on-hand. He said: “What you leave behind is not what is engraved in stone monuments, but what is woven into the lives of others.” This strikes a deep chord with me. Naturalists are often teachers, protectors of landscapes, and planters of flowers and trees. All of those actions have impacts far into the future. We live on as long as our actions ripple out into the world.

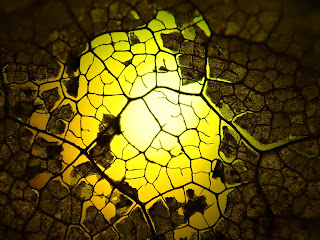

|

| Life and death, creation and destruction, are intertwined in the web of the Universe, as seen in these backlit leaf veins. Photo by Emily Stone. |

I was never an astronaut-aspiring space kid, but I did become enthralled with stars once I learned that they, like us, are born and die. Stars arise from clouds of dust, where gravity brings the particles together. Mass builds and gravity increases until hydrogen atoms smashing into each other combine to form helium. Nuclear fusion begins, light shines, and a star is born.

As the star ages and becomes a red giant, helium fuses into carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, magnesium, and eventually iron. But where does the rest of the periodic table come in? Those elements can’t be created during a star’s life. They are conceived during its death.

The heat and energy involved in a large star’s death—in a supernova—are enough to synthesize many more elements, which are all hurled into space to form a supernova remnant, also called a nebula. Nebulas are the birthplaces of stars, and also of planets like Earth. The atoms who coalesced to form the Earth now cycle endlessly through her rocks, her air, her water, and her life. We literally are made of stardust.

This story is reenacted over and over in nature. There can be no creation without destruction.

So, from a Naturalist’s point of view…from a worldview filled with connections and joyful reciprocity: Our veins course with stardust. Our muscles are built from venison. Our lungs converse with maples trees. Our bones swirl through the mud with herons. With every breath, with every bite, we are intimately connected with all the atoms on Earth. When we think like naturalists; when we allow ourselves to be woven into the web; then, as Mary Oliver writes: “life is real, and pain is real, but death is an imposter.”

May you find connection on this All Hallowtide.

Note: This article is a revision of one published last year at this time.

You can also view a video version of these ideas!

Emily’s award-winning second book, Natural Connections: Dreaming of an Elfin Skimmer, is now available to purchase at www.cablemuseum.org/books and at your local independent bookstore, too.

For more than 50 years, the Cable Natural History Museum has served to connect you to the Northwoods. The Museum is now open with our exciting Mysteries of the Night exhibit. Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and cablemuseum.org to see what we are up to.