Columns

of steam rose from the valley behind a curtain of dark green trees as we pulled

up to the trailhead. Five chatting friends tumbled out of the bright yellow Bombardier

snowcoach into still morning air. With the satisfying “click” of boots locking

into skis, and a few words about technique, we took off down the old

road-turned-ski trail.

From

the start I was distracted by tracks. The huge hind feet of snowshoe hares were

like exclamation points dotted by their tiny front feet. “SNOW!!!” They seem to

shout, and we joined in their enthusiasm. Pine martens had sewn dotted lines

over the drifts in their typical stitch of paired tracks at an angle to their

direction of travel. Red squirrel tracks visited each tree like a

connect-the-dots coloring page. Across the sparkling Fire Hole River, an otter

slide nicked the bank. All of these familiar friends made me feel at home.

Then,

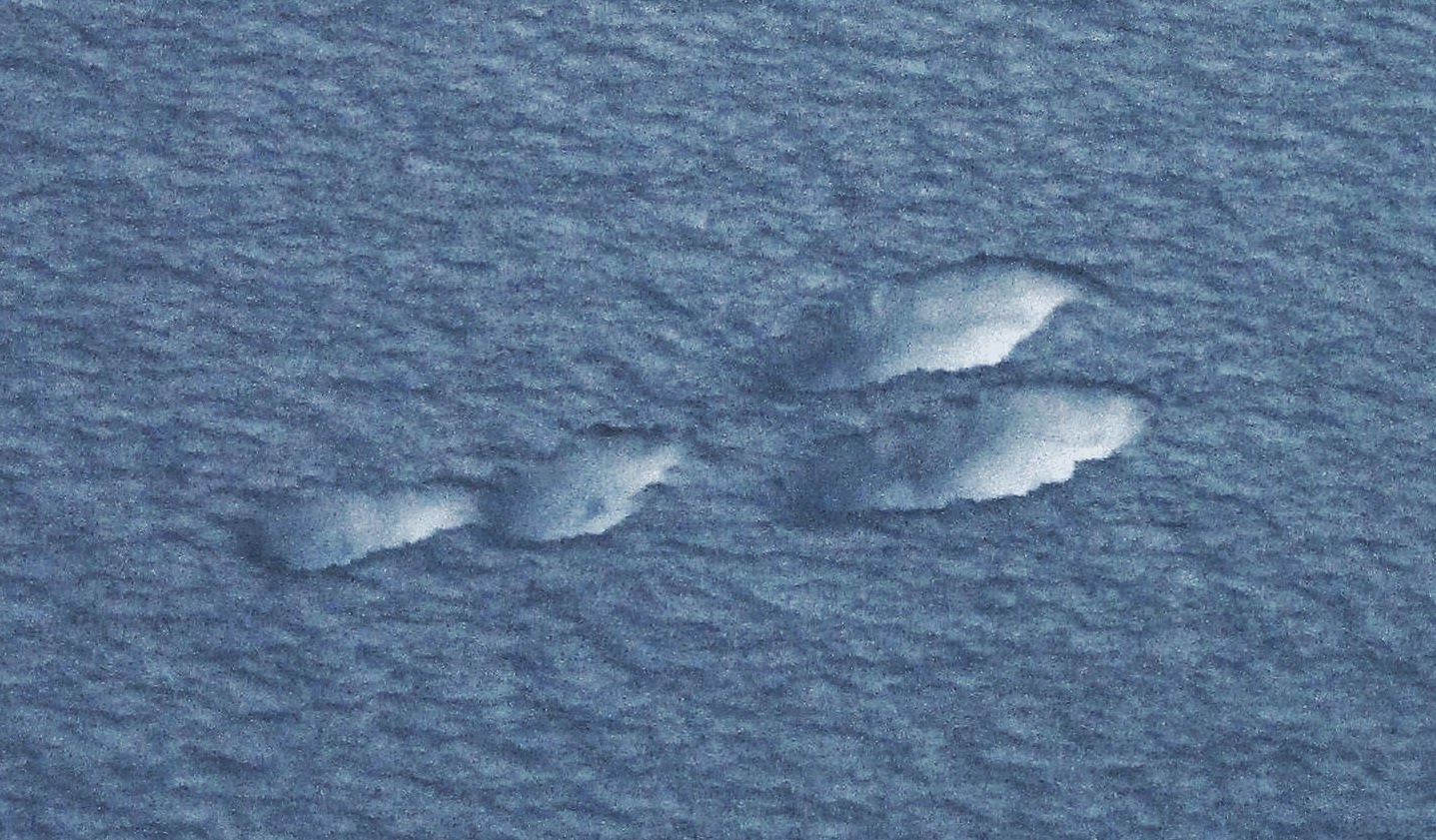

a large, messy trough of tracks entered from the woods, and started post-holing

down the center of the groomed skate lane. Too round to be boots, too big to be

deer, these tracks were from bison. I don’t see that back home! Here in

Yellowstone National Park, though, bison are more common than deer in the

winter, and the tracks of elk and wolves commonly pock the ski trails as well.

While

the animal signs were fun to see, they weren’t our goal for the day. At the end

of this trail sits the Lone Star Geyser. Named for its remote location – three

miles from its nearest neighbor (Old Faithful itself) – this is one of the

biggest geysers in the park. Its large cone, formed slowly by silica that

precipitates out of the water, chronicles a very long life.

Since

at least 1872, Lone Star Geyser has been erupting approximately every three

hours. It begins with a heat source – shallow magma chambers left over from one

of the largest volcanic eruptions known to have occurred in the world. Then water

– rain and snow – seeps into cracks, fissures and cavities in the rock above

the magma chamber. As the heated water begins to rise again, it may pool in an

underground reservoir capped by a constriction. Minerals from the water

precipitate onto the walls, making them pressure-tight. This narrow tube of

resistant rock keeps the water from rising freely, as it does in the many hot

springs in Yellowstone.

Water

nearest the surface does cool down, but it can’t circulate in the tight

quarters. Instead, it pressurizes the water below it like the lid on a pressure

cooker. Higher pressure means that the water in the chamber can heat to above

the normal boiling point. But it can’t heat indefinitely. The water nearest the

magma eventually starts to steam, and the resulting bubbles burst through the

geyser’s vent, carrying splashes of water with it. This reduces the pressure in

the whole system. The superheated water flash boils into a column of steam, and

erupts in a spectacular display of hydrogeology.

This

is exactly what was happening as we skied the last of our 2.5-mile route up to

the Lone Star Geyser. Steam billowed from the impressive cone, and water

splashed onto the barren moonscape of bare mineral deposits and snow. A dull,

frothy roar accompanied the spectacle. [View a video on the Cable Natural

History Museum’s Facebook page!]

As

we milled around the viewing area, taking photos, shooting video, and just

being amazed, some tentative sunshine broke through the clouds. In the steam

cloud, a rainbow appeared, and we couldn’t believe our luck. We skied back with

soaring hearts and full memory cards.

The

thick forests we skied through, with their plentiful wildlife and beauty, are

all protected because of what we just witnessed. Yellowstone has the world’s

largest and most diverse array of geysers, hot springs, mud pots and steam

vents. It was these features that prompted the creation of the world’s first national

park on March 1, 1872, and eventually led to the creation of the National Park

Service in 1916. While the animals we saw on the trip weren’t the goal of the

park, they have benefitted dramatically from its protection. Bison, wolves,

cougars, and more would not be here in this healthy ecosystem if it weren’t for

our fascination with the geysers.

In

my mind, that makes the eerie views of steaming valleys even more magical.

|

Great day to ski: The wide, flat road along the Fire Hole

River makes a great place to ski and chat with friends!

Photo by Emily Stone

|

|

| The Lone Star Geyser only erupts every three hours, and the sun only came out one that day. We were very lucky to see a rainbow in the steam! Photo by Emily Stone. |

|

| Snowshoe hares have increased in the park since the 1988 fires increased the regeneration of lodgepole pine. Photo by Emily Stone |

No comments:

Post a Comment