By Guest Writer JoAnn Malek

[JoAnn Malek is a long-time Museum member and a recent participant in the Natural Connections Writing Workshop. JoAnn has graciously fine-tuned an essay that she drafted during that class. It touches on realities we all must face at some point—for ourselves and our loved ones--and I’m excited to share it with you this week. –Emily Stone]

Our morning hike began on a steep downhill sidewalk laden with wet leaves, squished Osage oranges, errant branches, and jutting rocks. I was wary and careful, glad to have good eyes, new walking shoes, and sturdy trekking poles.

The trees above were lush, with leaves in more shapes, sizes, and greens than we find in a Wisconsin woods in October. Rocky ditches and muddy gullies carried trickles of water, a reminder of how this ridged, deep-valleyed hill country was formed. Raptors were using updrafts, soaring in the blue, but a bank of dark clouds was spreading across one section of sky. My rain jacket was at home.

[JoAnn Malek is a long-time Museum member and a recent participant in the Natural Connections Writing Workshop. JoAnn has graciously fine-tuned an essay that she drafted during that class. It touches on realities we all must face at some point—for ourselves and our loved ones--and I’m excited to share it with you this week. –Emily Stone]

Our morning hike began on a steep downhill sidewalk laden with wet leaves, squished Osage oranges, errant branches, and jutting rocks. I was wary and careful, glad to have good eyes, new walking shoes, and sturdy trekking poles.

The trees above were lush, with leaves in more shapes, sizes, and greens than we find in a Wisconsin woods in October. Rocky ditches and muddy gullies carried trickles of water, a reminder of how this ridged, deep-valleyed hill country was formed. Raptors were using updrafts, soaring in the blue, but a bank of dark clouds was spreading across one section of sky. My rain jacket was at home.

|

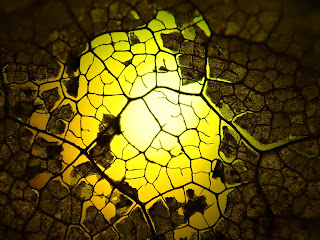

| The author admires a tree during her visit to Arkansas last October. Photo by N. Deegan. |

I had been touched to be invited along on a daughter’s family vacation. After several years of self-sufficiency, I was pleased to take a back seat for the trip through five states. My son-in-law brought two mountain bikes, to be used for different kinds of riding, apparently. This was a recreational mecca, after all. Grandson, daughter, and I packed hiking boots.

We continued walking into the Razorback Regional Greenway and emerged onto a flat sidewalk centered with a yellow line. I stayed far to the right, hoping my failing ears would perceive the approaching whirr of tires and the “on your left” warnings. Paths into the forest beckoned, but not for those without wheels and helmets.

Motion filled the woods. Riders leapt over hills, swerved around bermed corners, plunged down rock ramps, and roller-coastered through bumps.

Muscular adults peddled high-tech bicycles. There were daring, invincible teens, of course. But also small legs pumping, and mini wheels spinning. Parents carrying young ones. A group of young men in overalls, accompanied by young women and little girls wearing long skirts and lace caps. Teachers trailing school children. Even old women like me were riding.

There was much to watch as we walked, but I stopped short when an orange-spotted spider appeared just in front of me, hanging by a long, long thread. Thick ivory legs, a round ball of a body, and those pretty orange circles helped me identify Araneus gemmoides, a cat-faced or jewel spider. This species occurs throughout the Western U.S., including the Midwest, but I’d never bumped into one before.

Funny, but I found myself identifying with that brave, dangling thing. My long-time motto comes from Eleanor Roosevelt: “you must do the thing you think you cannot do.” I agree to adventures and accept challenges. That’s how I ended up on this tangle of trails in Bentonville, Arkansas. The spider had left the safety of the tree as I had left the safety of isolation from Covid-19.

At home, I care for a cabin and much that surrounds it, haul logs, tend a wood stove, and drive short and longer distances. I kayak, swim, hike, skate, and ski alone. The spider wove the thread that held her. I’ve woven one, too. Now we both cling to our independence.

When Jim became ill, our plans and dreams were cancelled. After his death, it seemed I’d been given another chance. But I had learned that any type of misstep can change everything. I’m fragile and vulnerable, like that eight-legged dangler.

Abruptly, a passerby severed the long thread. The spider fell gently to the ground and scurried away. Her journey had been altered. I expect that the threads connecting me to cabin life will one day be severed. Will that happen when it is no longer safe for me to drive? Will the aches and pains of an aging body prevent me from completing required tasks? Will an accident interrupt this life permanently?

I know, for now, that I can trust myself, but I must trust others as well. My children are watchful, always aware of my capabilities. They will help me continue to live in my happy place for as long as possible. When the thread of independence finally breaks, they will help me to move gently on to the next phase of my journey.

For more than 50 years, the Cable Natural History Museum has served to connect you to the Northwoods. The Museum is now open with our exciting Mysteries of the Night exhibit. Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and cablemuseum.org to see what we are up to.