Skulls of every shape and size lined the Great Hall as the troop of scientists bumbled in out of the swirling snow. Each paused in awe as they realized what treasures awaited them.

No, I’m not describing a scene from one the of the Indiana Jones movies. That’s how a group of Wisconsin Master Naturalists began a lesson on mammal skulls during our recent Wild about Winter Ecology Weekend.

|

| Cindy examines the flat face of a bobcat skull during a Mammalogy workshop. Photo by Emily Stone. |

This is the third year I’ve hosted a three-day program at the historic Forest Lodge Estate on Lake Namakagon in late January. We’ve drilled holes in the lake ice to sample zooplankton, dissected bluegills to find developing eggs, followed porcupine tracks into a culvert, and learned the intricacies of how various critters survive the winter. This year, the focus was on mammals.

Dr. Julie Ray, who earned her PhD studying snakes in Panama, and who founded the Project Northwoods Nature Center in Winter, WI, brought her extensive skull collection to help us get a feel for the diversity of mammals in Wisconsin. Julie often shares these skulls, and her knowledge, with the high school students in Winter.

I also share skulls with students, mostly as part of our MuseumMobile program that visits local schools. In the fall, I bring a tub full of skulls to the second grade classrooms, and we focus mostly on identifying herbivores, omnivores, and carnivores by their teeth. Herbivores have flat molars for grinding plants, and their front teeth might either be the sharp chisels of beavers and rabbits, or the bottom-only incisors of deer. Carnivores need sharp incisors, large canines, and serrated back teeth to help cut and tear their meat. Omnivores combine the flat molars with large canines so that they can eat a wide variety of foods.

Recently, when I made my second MuseumMobile visit of the year, I quizzed the kids. “So, if the mystery animal I’m about to show you is a carnivore, what would its teeth look like?” “So, if the fake scat I’m about to show you is from an herbivore, what would its teeth look like?” Little hands shot into the air so enthusiastically that I thought a couple of them might fall out of their seats. Turns out that the skulls had made an impression during my first visit, and the students had no trouble remembering what they’d learned.

Having never taken a Mammalogy class, though, I don’t actually know much more about the skulls than the basics I tell the kids. Julie began her lesson with some slides, and some ideas about how to infer an animal’s adaptations by the morphology of its skull.

For example, the zygomatic arch—basically the animal’s cheekbone—helps to support the eye, and also helps you get a feel for how big the animal’s eyes are. I’ve studied the eye sockets of owls and been amazed at their size, but I hadn’t transferred this observation to mammals. For example, itty bitty pocket gopher skull in Julie’s collection had a relatively small zygomatic process, along with its sharp rodent teeth.

|

| Pocket gophers have small eyes. Photo by Emily Stone. |

The location of the eyes is also important: predators have forward facing eyes for spotting prey, and prey animals have eyes on the sides of their head for a wider view of danger.

While cute, floppy ears aren’t preserved on a skull, a small ear hole—also called the external auditory meatus—can be seen near the back of the jaw. You can get some idea of how important an animal’s hearing is by the relative size of the hole. I was impressed by the relatively large external auditory meatus on the bat skull!

The external auditory meatus can be hard to find, but the foramen magnum (“great hole” in Latin) is much easier to see. This is the large hole where the spinal cord connects through to the brain. The orientation of this opening can help you figure out what posture the animal uses to walk. Except for humans, all the mammals in Wisconsin walk on all fours, so their foramen magnum is at the bottom and back of their skull. Humans’ is under the center of our skull, and chimps’ are in between.

The external auditory meatus can be hard to find, but the foramen magnum (“great hole” in Latin) is much easier to see. This is the large hole where the spinal cord connects through to the brain. The orientation of this opening can help you figure out what posture the animal uses to walk. Except for humans, all the mammals in Wisconsin walk on all fours, so their foramen magnum is at the bottom and back of their skull. Humans’ is under the center of our skull, and chimps’ are in between.

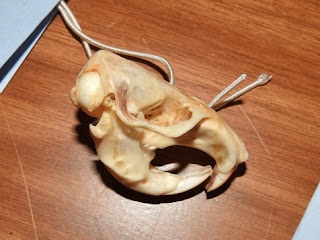

Have you ever compared the skull of a canid (dog family) to one of a felid (cat family)? Wild species of dogs and cats are some of our most well-known predators, and they eat many of the same prey, but their skulls look completely different. They both have the sharp, serrated teeth of carnivores, but wolves have a very elongated nose cavity, and cats have a pretty flat face. Why would that be? Canids use their sense of smell for hunting, and cats tend to sit and wait. Their adaptations and habits are indicated in their skulls.

Julie passed out dichotomous keys—which allow you to compare two options at a time until you’ve identified what you’re looking at. Even she gets impatient with the long process, though, and gave this advice: “Just count the teeth! Opossums are the only mammals in Wisconsin with 50 teeth. If the skull has a lot of teeth, you’re done!”

|

| An opossum skull is easily identifiable by its many teeth. Photo by Emily Stone. |

With this interesting lesson, and all of the skulls, there were a lot of smiles in the room, but I checked out her opossum skull, and sure enough, it showed me the toothiest grin of all.

Best of all, we didn’t have to dodge poison darts or tiptoe through a room full of snakes to find our Great Hall full of skulls. Top that, Indiana Jones!

Emily’s second book, Natural Connections: Dreaming of an Elfin Skimmer, is now available to purchase at www.cablemuseum.org/books and at your local independent bookstore, too.

For more than 50 years, the Cable Natural History Museum has served to connect you to the Northwoods. Come visit us in Cable, WI! Our new Curiosity Center kids’ exhibit and Pollinator Power annual exhibit are now open! Call us at 715-798-3890 or email emily@cablemuseum.org.