The

sparkle in his eyes and energy in his voice revealed Marc Hanna’s love of

telling the story. “Lamar Buffalo Ranch is like the Mount Sinai of the

environmental movement,” he concluded, “we got the tablets here.” The group of

writers and guides gathered around the table erupted in spontaneous applause.

After

a morning in Yellowstone’s Lamar Valley—“America’s Serengeti”—we were already

enamored with everything. Our knowledgeable guides, peeks of sunshine,

countless elk, eagles, coyotes, and herds of bison—visible as dark mounds

through the swirl of a passing snow squall—all combined in a kaleidoscope of

wonder.

To

top it off, we paused for lunch at Lamar Buffalo Ranch. These quaint, historic

buildings gathered next to a large corral date back to a very different time in

Yellowstone National Park—a time when the seeds of our current environmental

ethics were just beginning to sprout.

While

bison survived the mass extinctions of other megafauna at the end of the

Pleistocene, they fared much worse during the 1800s. Settlers, market hunting,

sport hunting, and a U.S. Army campaign nearly eliminated these majestic creatures—once

numbering more than 30 million—from our prairies.

Even

the creation of our first National Park, with security provided by the U.S.

Army, couldn’t fully protect the remaining bison from poachers. The Army’s “snowshoe

cavalry” built patrol cabins in the woods for their campaign against poachers.

They skied between huts on large wooden planks, called “Norwegian snowshoes.”

Four surviving remote cabins still provide housing for National Park Service (NPS)

patrols and researchers. But in the end, an even more dramatic approach was

needed to save the last of the bison.

With

just 23 free-ranging bison left in the park, the U.S. Army created a new herd in

1902, using pure-bred captive bison from ranches in Montana and Texas. The

cabins and corral at Lamar Buffalo Ranch were built to protect the new herd,

oversee their breeding, provide them with supplemental feeding in the winter,

and eventually propagate more than 1,300 bison by 1954.

According

to Marc Hanna, this marked the first time in history that humans had hunted an

animal to the brink of extinction, then taken a step back, desired the recovery

of the species, and fully facilitated their captive breeding and release. That

is why Marc called Buffalo Ranch the “Mount Sinai of the environmental

movement.” The ethics and values embodied in these old buildings still propel

our conservation efforts today.

Just

up the hill behind the corral, in a thick stand of trees, lie the remains of

one of the wolf release pens from their reintroduction just twenty years ago.

The Army’s campaign to save the bison was surely a precursor to the wolf

recovery effort. Today, wolves and bison rival each other for the title of most

iconic species in Yellowstone. What if neither had survived?

The

ripples don’t stop there. A thousand miles from Yellowstone, but just down the

road from my house in northern Wisconsin, there are reintroduced populations of

American martens and elk. Perhaps, according to Marc at least, any modern

effort to protect, increase, or release a floundering species can be tied back

to the small herd of bison once cared for by the Army.

With

such an illustrious history in the active stewardship of Yellowstone, it is

fitting that these buildings still have a role in inspiring conservation. After

the addition of old tourist cabins in the 1980s, and a remodeling project in

1993, Lamar Buffalo Ranch became a residential learning center. Middle school

students stay in the cozy cabins during their “Expedition: Yellowstone!” educational program put on by the NPS.

The

Yellowstone Association Institute also uses the campus for their Field Seminars

that combine “field excursions and classroom presentations to give you a

complete overview of the Yellowstone ecosystem.”

One

such class was working quietly in the back room as we opened box lunches and

listened to Marc’s story. Eleanor Williams Clark, a recently retired NPS

administrator, was sharing her expertise in keeping “The Artistic Journal in

Deep Winter.”

A

dozen or so students worked in a variety of media as Eleanor opened her

personal field journals for us. Vibrant colors of dried grasses, willows, and

wildlife shone from the pages, and herds of bison rumbled through the rainbows,

too. The beauty she captured was soul-grabbing, and would inspire anyone toward

conservation. The legacy of Buffalo Ranch continues.

Marc is

the campus manager for these Field Seminars, and plainly loves connecting

visitors to this amazing landscape and the stories it has to share. He does a

great job too; better than I can do from the outside. Maybe you should go visit,

and let him tell you the story.

|

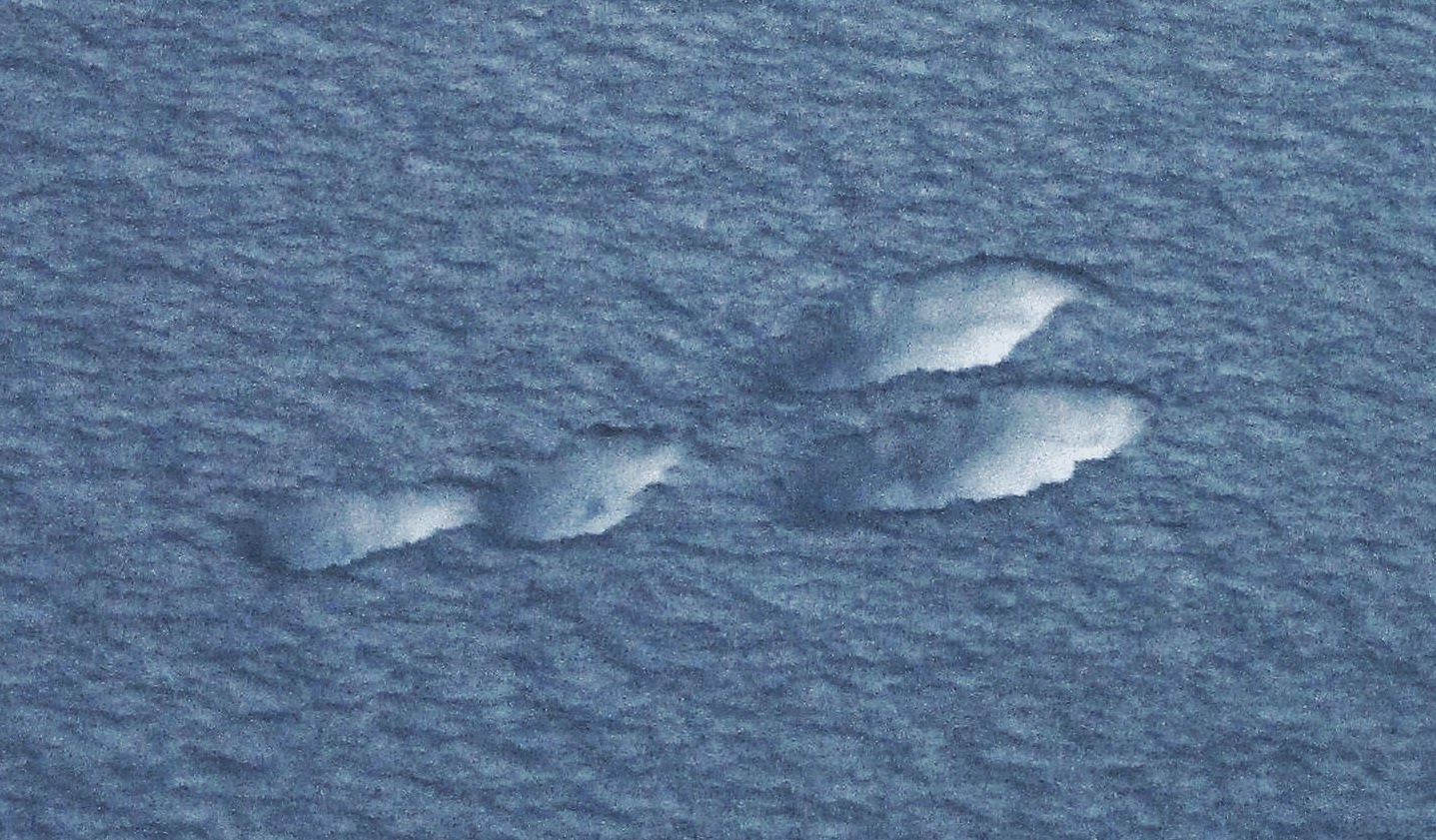

| The impacts of bison and their recovery make tracks all over the west, our collective psyche, and the ski trails in Yellowstone. Photo by Emily Stone. |

| |

|